I do have some regrets in life, and two of them are connected to an unforgettable evening in a hotel room in Vicksburg, Miss. What I mean is, I can't find the cassette tape of me playing music there with the blues legend Willie Dixon, or the handwritten lyrics he gave me as I was leaving.

I held onto those priceless items for many years, but I don't know what I did with them, and it's quite possible they got thrown away accidentally. Shame on me, I know. Hopefully, they'll turn up in a box or a tote at some point, but in the meantime, I'll tell you about them. This is a story that I've been carrying around for almost 38 years, and it's one of the coolest things that's ever happened to me.

For some background, Willie Dixon was a tremendously talented songwriter and musician. I think of him as a cornerstone of American music. He's best known for writing many of the absolute classics in the world of blues, a very long list of songs that includes "I Can't Quit You Baby," "Hoochie Coochie Man," "You Shook Me," "Little Red Rooster," "I Ain't Superstitious," "My Babe" and "Wang Dang Doodle."

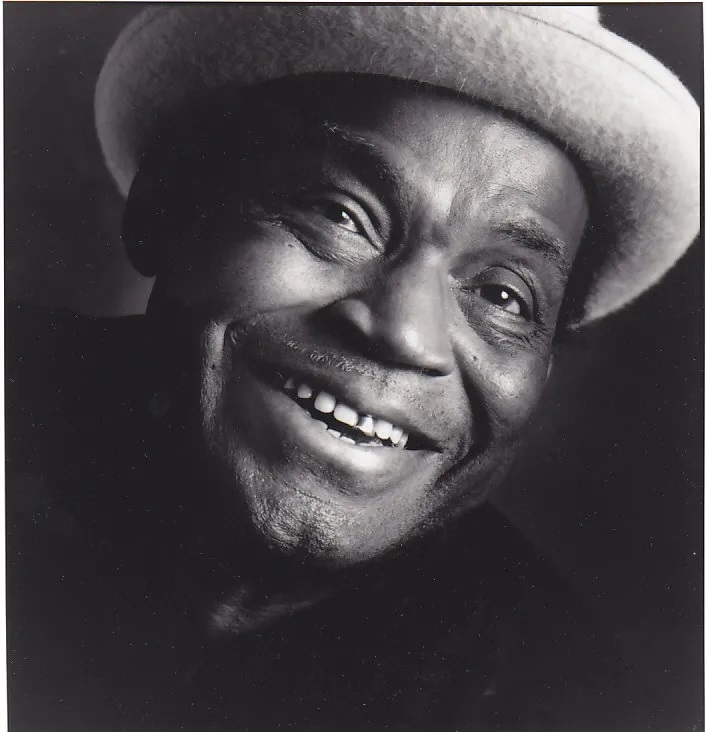

He was a big man with a booming voice who played the upright bass on lots of blues recordings and also on Chuck Berry's early songs like "Johnny B. Goode" and "Maybelline." In addition to being a songwriter and performer, he was the recording engineer at Chess Records in Chicago in the 1950s and '60s, so he played a vital role in electric blues. Many classic records by the likes of Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, Little Walter, Koko Taylor, and Otis Rush couldn't have been made without him.

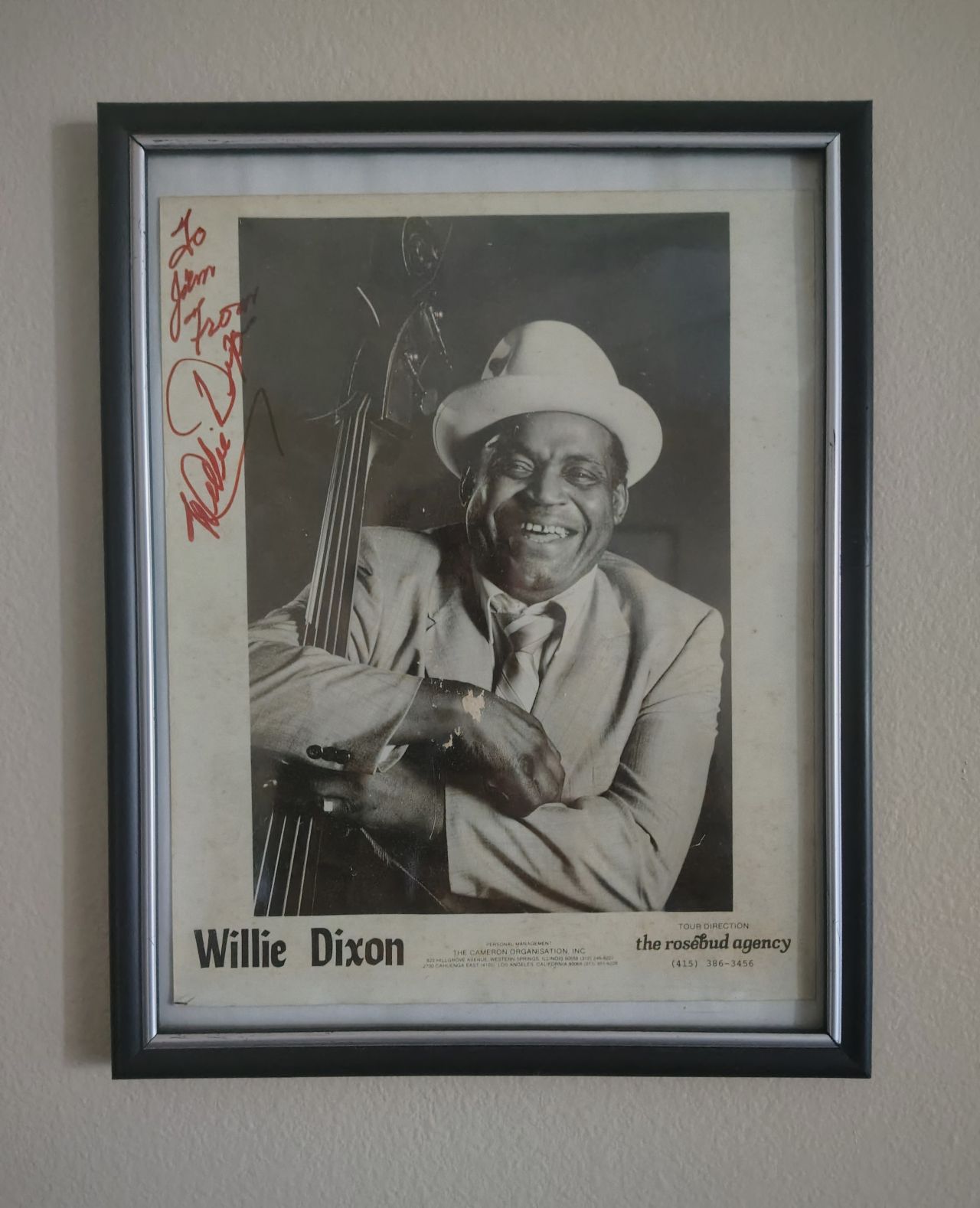

In late February 1988, I was pretty familiar with him, but I had no idea he was from Vicksburg until a professionally produced press kit landed on my desk one day at the Vicksburg Evening Post. I was a young reporter, just 23 years old at the time, and he was 72. According to the press release, he would visit Vicksburg Middle School soon to donate some band instruments on behalf of an organization called the Blues Heaven Foundation. Inside the folder was an 8x10 photo of Mr. Dixon and his bio, along with a dizzying list of dozens of song titles and the artists who had recorded him.

I gladly wrote an advance story on the event and covered his appearance in the school auditorium. After presenting the brass instruments, the stately Mr. Dixon addressed the young students, telling them how music could teach them about history and help them to understand the world around them. "Blues is the true facts of life expressed in song," I remember him saying. I don't know if I thought to look around and gauge the young students' reactions, but I know I was drawn in easily by his strong, genial presence and his obvious wisdom.

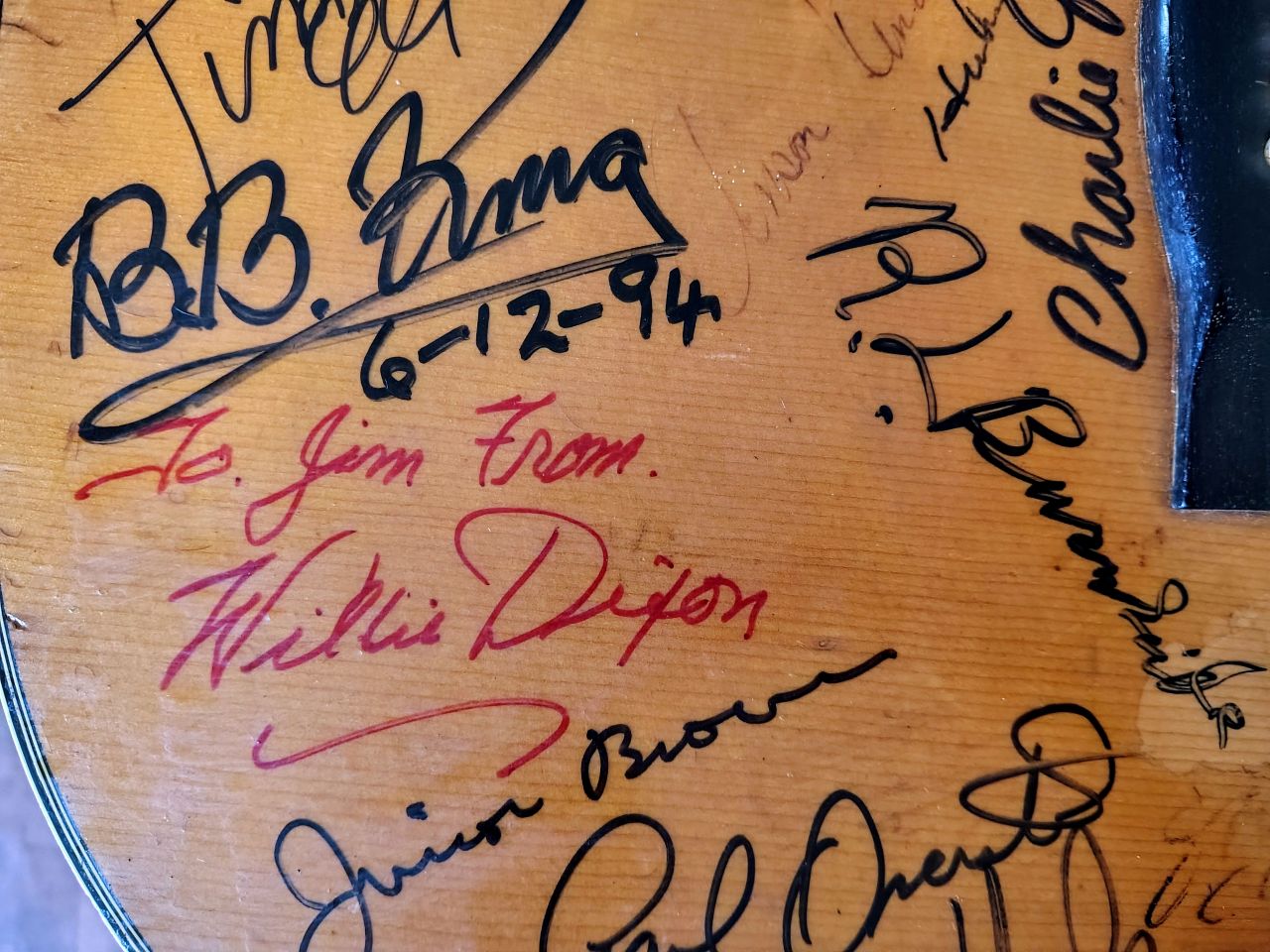

As the students and teachers disassembled, I introduced myself and spoke to him one-on-one. I had brought a few copies of the newspaper with the story I had written, and he readily autographed a couple of them, along with the promo photo from the press kit. I asked him to sign one of the articles for my friends in a popular band called Beanland. We were all delighted that he inscribed it to the "Beanland Blues Band" because in reality, they were more of a jam band with a kind of hippie vibe.

I was about to head back to the office and write about the school visit for the next day's edition, and figured this would be the end of my time with this legendary man, but I was wrong. He told me what room he was in at the Holiday Inn and invited me to stop by sometime over the next few days. He said a writer named Don Snowden, who was a regular contributor to the Los Angeles Times, was traveling with him, doing research for a book they were working on.

I went to the hotel the following evening. Still dressed in a suit but without a tie, Mr. Dixon had just gotten in from showing his co-author where he'd spent his early years before hopping a train to Chicago as a teen. He was quite cordial and seemed glad to have some company. Within a couple of minutes, he sat down and casually removed a prosthetic leg from inside his dress pants. "Sugar diabetes," he explained as I tried not to look surprised.

He was forthcoming and entertaining as I gently peppered him with questions about his life and career. After probably 30 minutes or so, I mentioned that I played guitar, sang, and wrote songs, and he reacted immediately. "You should go get your guitar and a tape recorder, and I'll have a song for you," he said. "You're a young man, and you're not married, right? I have a good song in mind for you."

My head was spinning as I quickly made the 20-mile round trip to the house where I was living outside of town. I grabbed my Yamaha acoustic and my Sony jam box to record with, and I hesitated just long enough to use the phone to call a buddy of mine, David Durst. I remembered that he had asked me to let him know where Willie Dixon would be while he was in town, so I made a spontaneous decision to invite him to join us. I knew it would blow his mind, but looking back, I think I must have wanted someone else there to witness this miraculous happenstance.

Back at the hotel room, Mr. Dixon had written the lyrics to "Every Girl I See" in his neat cursive on a sheet of paper from a yellow legal pad. He had also written his publishing information: Hoochie Coochie Music, administered by Bug Music, BMI.

With David easing into a chair in a corner, I tuned my guitar and strummed an A minor chord that seemed to fit naturally with the distinct 12-note melody that Mr. Dixon hummed. He slapped the lyric sheet percussively in a staccato rhythm pattern and reeled off the lively lyrics as I kept a steady single-chord groove. The tape was rolling as he described the various women in a crowd by rhyming their charms with the colors or patterns of their clothing. I won't type all the lyrics, but here are some examples: "The girl I see dressed in green, she's the finest thing I've ever seen; the girl I see dressed in red, she makes me fall down dead; the girl I see dressed in yellow, you know she's so fine and mellow." A couple of my favorites were "the girl I see dressed in gold, I love her with my dying soul" and "the girl I see dressed in silver, man she makes my liver quiver."

David and I sang along with him on the chorus, which was, "Every girl I see looks good to me." In a refrain, our band leader gestured as if he was pointing to different ladies in the audience as he sang: "You look good and you look good ... you do, too ... you look good and you look good."

It was amazing to see from the inside how he quickly but carefully crafted one of his catchy songs. He was showing me how to really deliver it, which is captured on the tape that I can't find: "You see, the good thing about this song is they don't know if you're talking about one or two or the whole crew." He was like that — in addition to being smart, smooth, and sophisticated, he was so musical that he sometimes spoke in rhythm and rhyme.

I thought for a while that he created the song from scratch in the time it took me to go home and back. Later, I found out that Buddy Guy had released a version of it in 1967 (but most of the lyrics are completely different). I have played the song myself over the years, but despite Mr. Dixon's instincts, I never felt that it was a great fit for my personality. I made a few copies of the tape and handed them out to a few friends, including David, whose voice was clearly audible on the choruses. That was a real treat for him because he wasn't a musician at all, just a big fan of music.

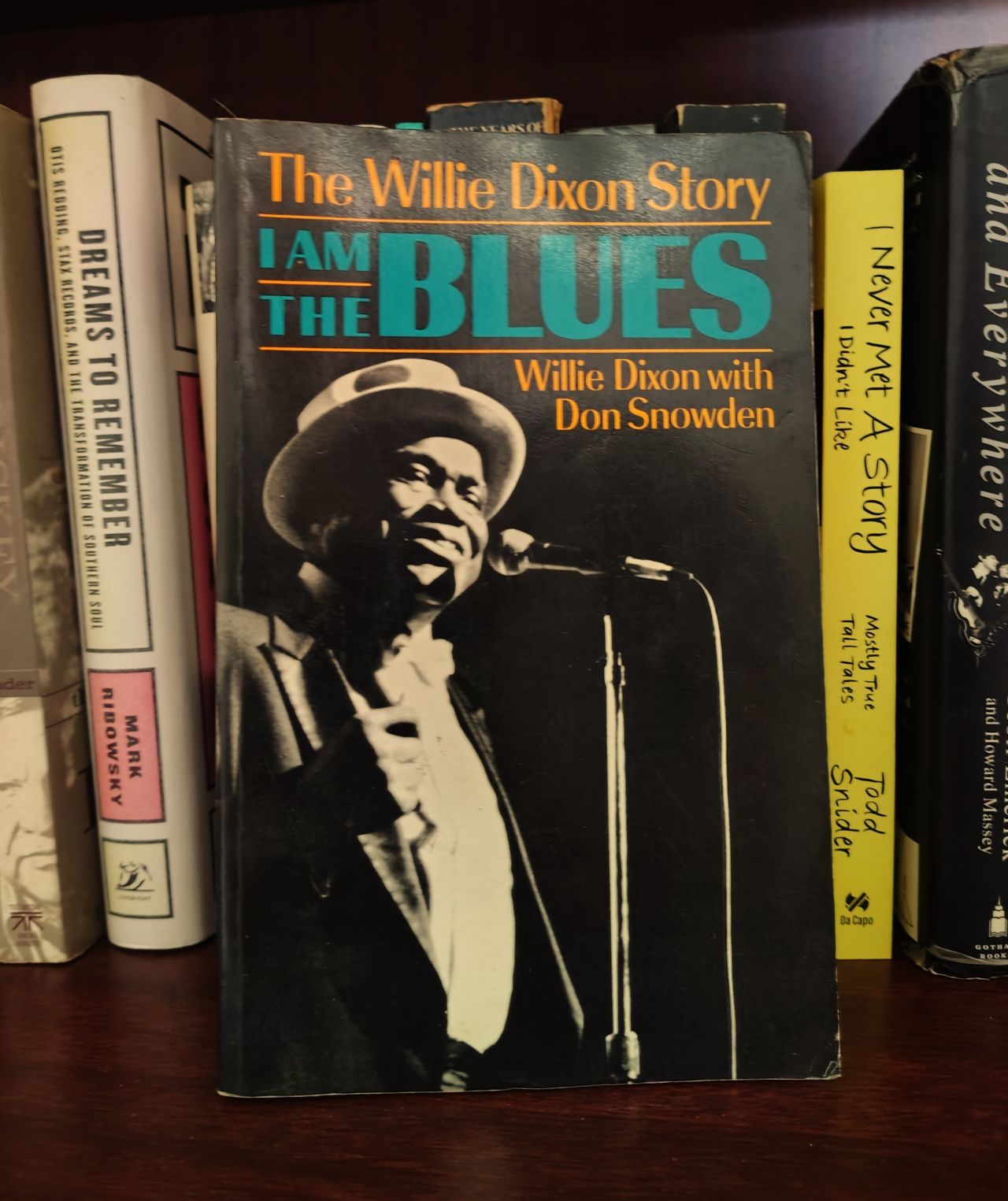

That's pretty much the end of the story, except for a funny footnote that happened almost exactly three years later. By then, I was living on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, and my photographer friend Stephen Anderson and I went to New Orleans to check out the Aquarium of the Americas, not long after it opened. After touring it and taking pictures inside, we walked up toward the French Quarter and stopped for traffic at the foot of Canal Street as an older-model Chevrolet Caprice or Impala slowed down to take a left onto North Peters Street. I looked over and spotted Willie Dixon in the back seat, plain as day, with his distinctive white hat and his brass-handled cane. "There's Willie Dixon in that car," I said to Andy, and he scoffed back with, "Yeah, right." We watched as the big sedan slowed to a stop close to the curb in front of Tower Records. It was him, all right, along with his daughter Shirli, and they were arriving for a book signing event for "I Am the Blues." Seriously, what are the odds of that happening?

Andy still had his camera in his hand or around his neck from our visit to the aquarium, so he snapped a quick shot. I was so excited to see Mr. Dixon again that I kind of embarrassed myself as I enthusiastically recounted our amazing interaction in the hotel room in Vicksburg. As I went on and on with the details, I started to realize that others had been lined up inside the store, their new books in hand, patiently anticipating their own exciting encounters with Willie Dixon. Some of them, understandably, were annoyed that I was dominating the situation, though I didn't mean to; I was just caught up in the excitement of running into him again. I also realized, sadly, that it was clear that the blues giant I had grown to admire so much had absolutely no memory of me or our earlier interaction. He looked me in the eyes, offered a slight shrug and a sympathetic frown, and said simply, "I meet so many."

A similar thing happened the second time I met Bo Diddley just a few years later. But that's another story.